Code

library(ggplot2)

target <-

ggplot(data.frame(c(1:10),c(1:10)))+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 71.5, color = "black")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 70, color = "#99cc66")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 60, color = "white")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 50, color = "#99cc66")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 40, color = "white")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 30, color = "#99cc66")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 20, color = "white")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 10, color = "#99cc66")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), size = 4, color = "white")+

ylim(0,10)+

xlim(0,10)+

theme_void()

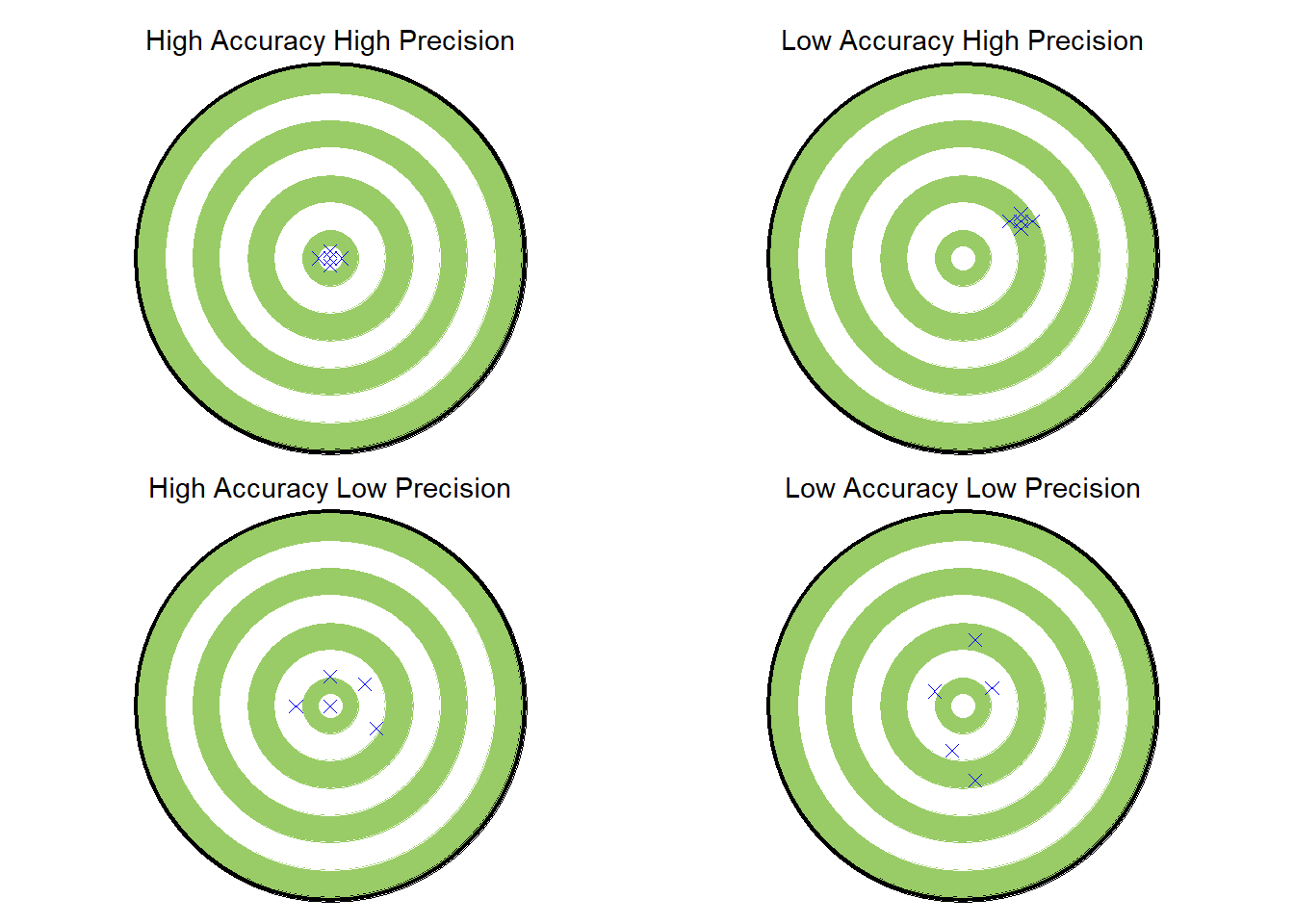

hahp <- target +

labs(subtitle = "High Accuracy High Precision")+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5))+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5.2), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 4.8), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 4.8, y = 5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.2, y = 5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")

lahp <- target +

labs(subtitle = "Low Accuracy High Precision")+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5))+

geom_point(aes(x = 6, y = 6), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 6, y = 6.2), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 6, y = 5.8), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.8, y = 6), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 6.2, y = 6), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")

halp <- target +

labs(subtitle = "High Accuracy Low Precision")+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5))+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5, y = 5.8), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.8, y = 4.4), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 4.4, y = 5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.6, y = 5.6), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")

lalp <- target +

labs(subtitle = "Low Accuracy Low Precision")+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5))+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.5, y = 5.5), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 4.5, y = 5.4), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.2, y = 6.8), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 4.8, y = 3.8), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")+

geom_point(aes(x = 5.2, y = 3), shape = 4, size =2, color = "blue")

library(patchwork)

(hahp | lahp) /

(halp | lalp)